|

|

|||||||||||||||||

|

|||||||||||||||||

|

|

|||||||||||||||||

|

|

|||||||||||||||||

|

|

|||||||||||||||||

|

|||||||||||||||||

|

|

|||||||||||||||||

|

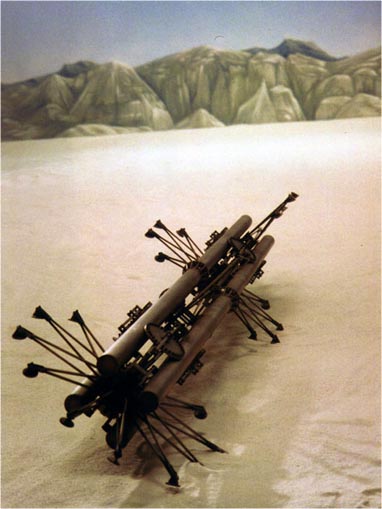

Far off in the endless plain the late afternoon sun is reflected in a metal

object. The old Asian farmer looks up and gazes into the distance

towards the place wherehe saw the thing flashing. He leaves his tools on

the ground and walks towards the handful of huts huddled together in

the solitude of the Tarim basin. "The wheel! The machine, it's coming," he shouts in the direction of the huts. A woman emerges from one of the huts with a boy of about ten. The old man points into the distance and repeats: "The machine is coming." The three of them gaze in the direction of the barely visible metal object that flashes in the West under the evening sky. That evening the old man tells his grandson about the machine that has been travelling across the Tarim plain at a speed of 18 mm per day for as long as anyone can remember. No-one knows where the object comes from. Sometime or other in the West on the edge of the great basin of land it began to move slowly East. Generations of folk had seen the wheels crawling slowly past under its own power; the machine became legendary and was a permanent landmark for the inhabitants there as they cultivate their fields year in year out. "It is moving in the direction of our village," the old man says, "it will be years before it passes our house. You will have to tell your grandson that when he builds his hut he will have to take account of the machine so that it can go on its way undisturbed." And the grandson did take the machine into account and his grandsons and granddaughters did the same and the wheel continued on its endless journey across the Tarim basin. This is roughly how the artist Gerrit van Bakel told me his story about the Utah-Tarimconnection. The project which he had been working on for years and which is so typical ofhis artistic approach and of the precision and openness of his designs. Right: model of the Tarim machine (set foto from film 'Time Machine' by Erik van Zuylen, 1994 |

|

|

|||||||||||||||

|

|

|||||||||||||||||

|

The Utah-Tarim connection links two huge level stretches of the

world's surface: the salt flats of Utah in America and the Tarim plain

inAsia to the North of Tibet. On the salt flats in Utah world speed records are broken by rocket-like vehicles. The immense land mass of the Tarim basin on the other hand is almost unknown. Van Bakel devised two machines for both regions that would take up the challenge of the prevailing situation in these two plains. As in the paradox of Zeno, the Utah wheel (inv. Nr. 179) takes on the high-speed monsters with its own speed of 18 mm per day. The machine for the Tarim basin (inv. Nr. 230) crawls at about the same speed across the 1100 km. of this plain and will, according to Van Bakel's calculations, take about 30 million years over it.*1 Time, speed, energy, movement, space and construction design are the ingredients of the Utah- Tarim scheme. The salt flats in America reflect modern technological culture's desire for speed. It is a place where technology challenges its own frontiers, unstoppable and insatiable in its aim togratify its own creator's competitive drive. Van Bakel's Utah Wheel (inv. No. 179) deflates this addiction to technological omnipotence and shows how beautifully a wheel can function in itself in the same space. A simple wheel moving under its own power, filling this vast space and mastering it with spirit, laconically exposing the pretensions to high speed as a sham. How different in fact from the vehicle designed for the Tarim plain. No competitiveness, no speed even, hardly engaging with time at all any more the machineadvances millimetre by millimetre towards nothing, against nothing and without any purpose like the slow clock of nature itself, a geological time-machine. There is another spirituality at play here. The path that the machine traces, like a plough whose soil is time, makes the space that it leaves behind it immaterial. The wheels that process space creates at the same time a new spiritual depth in its wake. For the scanty inhabitants of the plain who in the course of years have seen the wheels pass the plain will never be the same again; previously it was no more than a geographical measurement of length and breadth intended for the production of food. The track that has now been scratched there refers for ever to the slow wheels. The grandchild of one of the inhabitants would easily be able to cover the distance that the machine took years to move. A distance that through the track traced by the wheels separates him from his ancestors. Already his desecendants stretch forward towards the horizon. His time contracts spatially and he is astonished by the simplicity of things. The last conversation that I had with Gerrit van Bakel took place a couple of weeks before his untimely death; we met in his home-studio- factory tucked away in an isolated spot in the countryside around Deurne in the East of Holland. After driving back and forth through the town and asking the way three times I found the place where he lived and worked. In the tiny kitchen surrounded by an indescribable mess was a large cherry pie which he straightway cut up into generous slices to go with the coffee. Once again the theme of our discussion was our shared enthusiasm for the relation between art and technology and we hatched plans for possible new presentations. He definitely showed an interest in the ideas which he had heard about which were brewing in the Hague and he wanted to have more contact. We talked about the influence of the 'countryside' and of the significance of nature for art. Both of us came from farming families; he is from de Peel (sandy countryside in the North of the province of Limburg) and I come from the Achterhoek region in the East of Holland and we had both experienced the effect of the fields; we understood the notion of the geological clock that also guides and controls agriculture. The Utah- Tarim connection suggests an ecology within which technology is slowed down in order to integrate it with the tempos of nature. Not in order to return to an older mechanics but rather with a view to promote advanced ideas about a non-industrial technology that is closer to the old way of thinking in which art and science were not separate. In fact technology provides the simplest possible model of the operations of nature. Even the most complicated electronically controlled machines are in reality only experimental models, a function that is concealed by their stringently imposed practical functions. And this usefulness of technology that is apparently so indispensible also effectively clouds our view of the way that nature works within these technologies. The German physicist Heinrich Hertz showed the function of electro-magnetic waves and this extraordinary discovery was eventually given an alienated and useful form, that of the 'radio' that keeps us informed about everything but which also contains a concealed instructive function as a model of nature. It would seem that in exposing the hidden functions of nature the poetic-naive approach of the artist is just as effective as the logical-analytical approach of the modern scientist. Nature opens up just as readily to a poetic analysis using the resources of art as it does to a logical analysis that can lead not only to knowledge but also to exploitation and destruction. Art as an unusual form of natural science, a form of knowledge that from time immemorial has attempted to discover the hidden depths of nature by way of mythology and through innumerable works of art, is in fact a precious additional source. That afternoon we talked about the need to make a new definition of visual quality in response to the poverty-stricken picture that the media send out every day in response to a supposed demand for information. The relation between information and the quality of imagery is interpreted in a different way by the media than in art: 'beautiful' images must not be allowed to interfere with a mass audience as it assimilates its overdose of information. TV denies its own technical possibilities and would seem to opt for a lowest common denominator of ugliness. There is masses of material, so it must be dealt with quickly and not be made too complicated -that would seem to be the idea behind all this. At the end of an enjoyable day Van Bakel showed me his work in the rather dark factory space next to his house and I was once again astonished by the extraordinary feeling of industrial labour that is such a typical feature of the external appearance of his work. A genuine machine hall full of equipment and products. From my point of view as a composer it presented a strikingly concrete picture. In the huge space I recognized a number of objects that I had seen in photos. On leaving him I told him I considered him lucky to have the peace and quiet to work outside. He responded by grumbling about the noise that all the young people made with their motor bikes and then he showed me out. He walked with me to my car. On the way back I thought about the things he had told me and the objects I had seen.The objects of course were essentially different from the musical material that I was accustomed to working with. It could not even be compared with the technology of electronic music, but his ideas and his way of thinking did show a great resemblance to mine. Were art forms beginning to come closer together as a result of an increasingly generalized artistic consciousness? Universalism? In actual fact the different forms of art do not in my opinion need to come closer together. Crossing a boundary is something quite different from breaking these boundaries down. I couldn't imagine any music accompanying Van Bakel's machines, let alone electronic music. What was the common factor then? The road cut across the darkening landscape of de Peel as the Autumn evening drew to a close. In terms of their appearance Van Bakel's machines or 'things' Iink up with the mechanical constructions that 18th and 19th century engineers and scientists designed. Constructs that functioned as a result of movement and power in combination with solidity. Van Bakel rejects the restructuring of the mechanical tradition that has taken place in order to enable it to fit in with 20th century high-tech developments which rely more on speed and on the support of electricity. This rejection however is only an apparent one. He is thoroughly aware of new technological developments and also uses aspects of them in his own work. His silent, unpretentious and cerebral machines are however clearly quite different from the dynamic concept and often aggressive use of technology that one finds in performance groups such as the English Bow Gamelan group and the American Survival Research Laboratories. (The latter group even attempts to compete with the technological research carried out by the American army.) Taking as his point of departure the field of mechanical forces that operate in theworld according to Newton, Van Bakel works with concepts that turn the concrete conditions within this (gravitational) field backwards towards a world of forms whose purpose is the production of immateriality, of spirit. The other side of the mechanical universe of Newton and Descartes that is accepted by technologists only in the form of the abstractions of mathematics. An abstraction that now ends up in the fever of information science and hard computer technology. Van Bakel's machines are clearly neither calculators nor computers; they are however the result of mechanics and algebra. And, of course, of money. They are the result then of these 'three monsters of contemporary civilization' as Simone Weil called them. But his machines also have a relation with something that is essentially different and this is not just because they are art works. In the first place just as with Descartes and Pascal, they are the consequence of dreams. Fireside dreams about a harmonious unity of knowledge and world. The dream that was however later incorrectly interpreted so bringing disharmony into the world. Van Bakel's apparent recollections of the mechanics of a former age point to a heroicattempt to reformulate the old basic premises of mechanics and crucially to put them on show employing the same means and knowledge. His constructions would then seem to be mediators whose aim is to bring about a harmony between knowledge and nature; they operate from an imperative fire out of the depths that cools down and is transformed on attaining the open surface of his poetic-mechanical forms. He also makes a conscious use of the term harmony in relation to the effect that his work aims to achieve. Not directly an effect that is productive of harmony: it is rather a case of raising the whole question of the relation between man and machine. A relation that according to Van Bakel is disturbed and which is the historical result of people's fear of the natural world that surrounds them and which they experience as hostile. Objects were devised to keep nature at a distance and under control. This has succeeded splendidly due to the development of technology. The fact that over a fairly short period of time our original contact with nature has become lost apparently also has a negative influence on our relation with our own appliances themselves. And the more complex the design of the appliance the greater the distance between it and its maker. The isolation of the individual and the fact that he is cut off from his original (natural) sources, together with the rapidly advancing process of alienation from the technological world comprises in his opinion a central problem for the modern social system. It is a question whether the popular notion of 'interaction' or the designing of so-called 'human interfaces' will really reduce our alienation from the technological world of objects which has already become fairly autonomous. In this field of disturbed relations Van Bakel attempts to present his machines as viable backward steps for technological thinking. If the basic premises are formulated once more the individual is given the chance to adapt to the increasingly technological character of our society. Van Bakel once went as far as to make proposals for a complete reformulation of the world. A design with new plans for cities, ships, houses, furniture, children's toys, etc. A model for a society of individuals who will then be able to fulfill their aspirations to be technologically creative. He abandoned this plan after a while however. Perhaps the complex notion that Heidegger discussed because of his fear of 'the accelerating pace of technology' plays a role here too. The 'internalized' violence of industrial society with its tendency towards unlimited production. Heidegger's criticism derives amongst other things from his fascination with the 'holiness' of poetry that is not subject to the 'loss of being' (Seinsverlust) produced by the technological world. He regularly refers to artists such as Cezanne, Van Gogh, Rilke and H–lderlin. Rilke 's dislike of modern technology and his concern with the loss of the soul in things is taken up by Heidegger.' Only poetry (for poetry, read art in general) is capable of maintaining the value of things and the value of our own being. Rilke's concept of 'the growing invisibility of the world within us' which he expresses in the Duino Elegies returns with gathered force in Heidegger's notion of an 'inner world, an internal certainty that does not require any protection' where poetry strengthens the domain of the heart. This should lead to a new 'elevation of the things' a 'rendering the world symbolic' by way of the poetic potential of art. Its capacity for immaterialisation. The present position of what is called technological art would seem to be in strident contrast with this. It might make Heidegger turn in his grave, it is however a noteworthy tendency. After a hesitant preamble in the 19th century it would seem as though an acceleration is now occurring in the acceptance of the employment of new technology in artistic thinking. The metaphor-producing machine of the art of the beginning of this century has now been replaced by a systematic use of 'more highly organized materials'. Because that in fact is what is taking place. After a long period of time in which elementary materials such as stone, wood and metal were worked and used in art, one can now speak of a surge in the increasingly widespread use of more highly organized materials such as those of electronics and precision engineering; these are pushing art in a new direction. Making the Earth invisible and internalized now seems possible with the growth of the fearful 'internal violence of the Cartesian world'. (During a visit to the aviation exhibition in Paris in 1912 Marcel Duchamp told his friends, Leger and Brancusi, that 'this is the end of painting. Who could make anything better than this propeller!') Either art has surrendered to the progressive soullessness of the world or else something exceptional is taking place. An exceptional bond that threatens to emerge between poetry and the 'technological'. Provisionally I would assume that the latteris the case. Would Van Bakel's technological art or computer music for instance, confirm Heidegger's hypothesis of the end of the world, or would he perhaps even welcome the current complex relation between art and technology as the 'Anfang' or beginning of a new adoption and 'elevation' of technology or rendering it symbolic by means of poetry? Already 80% of the music that is broadcast by the media, is produced by computers and nobody experiences this as meaning the end of the world. And that technological art is capable of moving people is also no secret; Van Bakel's work is proof of this. The predicted end of the world would seem rather to be the end of the doom mongering of Post-modernism that is now (elaborating on Heidegger) breathing its last. A deliberately entered on alternative relation with technology as a 'material mirror of self-realization' gives individuals such as Gerrit van Bakel the possibility of making a creative contribution to a much needed open process in which the social introduction of new ideas and technological forms can be directly raised for discussion. Van Bakel shows that art is a good example of how individuals can introduce aesthetic ideals in a technological form into society so that in the course of time they can be judged for what they are worth. Moreover the separation between idea and perception, which the artist and the viewer are always left with as isolated experience, reveals the perceptible object, the 'work of art' that is, to a still greater extent as pure technique frozen into form. Automobieltje (inv. No. 180) is a good example of a personal reformulation of a 'self-mover'. Here the automobile is no longer an article of mass consumption, designed by large-scale organizations which everybody uses as a means of transporting themselves, but is the result of individual design. A personal shape given to the idea of the capacity for self-propulsion. But then with very specific basic premises such as: the devising of a form of transport that no children can be run over by, etc. This process requires not only extreme creativity on the part of the maker but also furthers social communication between the people who devised it. Communication about the best and most personal form that transport can take. One advantage is that technology will less easily escape our ability to comprehend it by becoming miniature in size. The miniaturizing of complicated technology leads to it disappearing from view and so it escapes our comprehension. The historic discoveries now lie hidden within the highly sophisticated and differentiated structures of high-tech design in order to promote what is functional and saleable (like Hertz' radio). For most people who use it, high-tech is a total mystery conceived and produced by industrial organizations that tower above us and that remain a world in themselves. In this respect Heidegger's fear was perhaps well-founded. We are offered useful objects from above in the form of products of mass consumption that we would perhaps rather have in a completely different form, one more appropriate to our personal needs; a washing machine that washed better without electricity or soap powder, clean and colour-fast at a temperature of ten degrees using biologically treated waste water. An ideal solution that industry could hardly begin to imagine. The fear of technology often turns into hate. Hypocritical because it urges one not to use it without creating the conditions where that would be practically possible. The important thing here is to bear in mind that industry is also the bringer of a very high level of techical sophistication and efficiency that satisfy the needs of large groups of consumers. This high level is however related to mass production, to competition and the maintenance of levels of profit. Van Bakel's constructions are obviously reformulations of old functions that are too often hidden behind attractive and glossy industrial packaging. But this in itself does not make his work art. Art can refer to a possibly ideal situation but works of art function in the first place for themselves. On the return journey in my own mass-produced little car with Nijmegen behind us we converged with many of our own kind; after half an hour in a long traffic jam stinking of exhaust fumes we once again achieved the speed that the car factories are so keen to advertise. In the midst of the beautiful open water meadows the motorway displayed its proud dead straight character with its promise of high speed next to the slow meandering silver line of the river IJssel. Van Bakel's constructions are often conceived of in open spaces of this sort and their almost functional form is what to a great extent defines this space. On the one hand this would suggest that they are a further development in the tradition of engineering and mathematics that strives to master space. On the other hand in their own context they testify to the kinship that Van Bakel felt with the natural countryside where he spent his youth. During our discussion however I had the feeling that another factor was also present which I was unable to formulate right then. One that played a decisive role in his work. Something that I was not directly aware of in earlier conversations was the phenomenon of 'temperature' that he certainly often mentioned when discussing an object but which he did not enlarge on in detail. From another quite different point of view I myself had been interested for a number of years in something that has become an increasing preoccupation in artistic thinking: the element of 'time'. Time, that is, in relation to temperature. In my own field, that of electronic music, time can be understood as a product of thinking about the physical property known as 'entropy', that is the irreversible decline in temperature in closed systems. Electronic music when seen as an artistic branch of information theory can be traced back to the research into thermo-dynamics carried out in the 19th century by figures such as Carnot, Maxwell, Clausius, Helmholtz and Boltzmann. This theory of thermodynamics associates time directly with entropy as a general temperature process. Time is then the expression of the gradual decline (in temperature) of the structure of the world. The death of matter as a direct result of its birth. Cybernetics and information theory attempt artificially to eliminate entropy from their systems with inbuilt control mechanisms. In a certain sense 'art works' also reveal the (unconscious) struggle that is waged against this process of decline. Life itself and spirit as a 'strange' phenomenon in this life transform lower energy by bio-mechanical means into a higher order (nature and culture) and so bring about a small reduction in general entropy. *4 Culture can then be conceived of as our answer, increasingly widespread and persuasive as time passes, to the gradual 'suicide' of the universe. When I first saw the Sorrow of Albinoni (inv. No. 184) (it's quite a pleasure to be able to see Albinoni's sorrow!) I had a strong sense of recognition. All the ingredients were present: a steady source of light, sound, fire, mechanics and entropic gas. And a visual process requiring 'time'. Not so unusual in performances, but Van Bakel's experiment did not have that artistically forced quality of many performances. The Adagio of the 18th century composer Albinoni that musicians regard as the clichÈ example of typical Italian melancholy, the kind of sentimentality that one associates with some films, is incorporated in Van Bakel's scientific- looking experimental set-up in a way that is both sobering and moving. A set-up however that 'fed' the poetic depth of the idea back to the maker himself in a way that was quite astonishing. Van Bakel talks here about what happened once when he had a strong urge to look into the beam of a laser: 'What did I do, I went and looked along the beam, I knew that it was dangerous to look directly into it. So I went right up to the source of the danger, I let the blue beam touch me, with the idea in mind that blue is a spiritual colour... As a result of doing this I have had a number of dreams. These dreams were repeatable... By using a fixed ritual to look into the beam I had dreams about things, about appliances that did not exist. A sort of self-hypnosis in dreams...*5 |

|||||||||||||||||

|

|

|||||||||||||||||

|

|

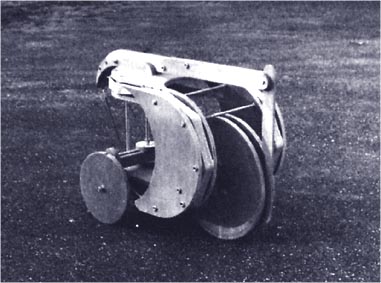

He added that he saw new projects in these dreams, quite concrete

constructions made of various indivisible materials. An amazing story. A melancholy installation is invented that in turn provides its maker with dreams by means of a ritual, dreams that are themselves about mechanics and machines. Descartes couldn't have thought up something like that, not in his wildest dreams! Temperature and climate recur regularly in Van Bakel's concepts. Particularly good examples of this are the 'Day and Night Machine' (1975), 'The Summer Wheel' (1982), 'Stradivarius Effect' (1979), 'The Winter Trolley' (1982), 'About Cold' (1983), 'In Search of the Source of Albinoni's Sorrow' (1979), etc. Temperature plays a part in the operation of his machines depending on the physical properties of certain materials that react on the situation that the object finds itself in. The 'London Machine' (inv. Nr. 196) is a good example. Left: London Machine, 1978-80, inv. No. 196 |

|||||||||||||||

|

|

|||||||||||||||||

|

As in the case of models in physics, the construction makes the

materials sensitive to influences from outside: climate, moisture, light,

warmth. The materials react to these varying influences and to each

other and start the construction operating. The construction produces

situations that maintain its own mechanics, that produce meaning and

provide continuity. The measurable variations in the materials within the

construction do not in themselves provide any useful information, either

about the world outside or about the situation within the construction.

One can get information from them but one can also let them be. The

machines produce their own existence, in the dimension of time and

strictly for themselves. It is possible for the viewer to observe this process.

'In the first place my machines produce spirit,' Van Bakel said.

Something that requires a considerable imaginative effort on the part of

the naive viewer who is used to thinking of 18th century mechanics in a

different way. The general idea that lies behind his 'things' beginning with the Day and Night Machine (inv. Nr. 162), is probably that of showing how the physical operation and transformation of different forms of matter can be brought to a higher level of complexity (spirit) if time is compressed. The construction makes it possible for materials to combine and to operate in service of this higher level (of thought). This makes one think of the attempts of the alchemists of former times; they are therefore essentially different from the constructions of classical mechanics which were intended either to provide knowledge about nature or else to be directly functional. Van Bakel's machines transcend this goal of practical usefulness and extend our understanding (of nature, if you like) to the hidden relation between the inertia of matter and the dynamics of spirit, but they give an insight particularly into the way in which negative entropy comes about. A function that every work of art possesses in theory, but with Van Bakel this referral to deeper and higher levels works like a process that has been deliberately staged. The often barely detectable alterations of the materials within the construction create a poetic power that works in combination with the processes of physics. It is actually a process of transformation. Transformation in the sense of Rilke's concept of 'internalizing' and 'rendering earthly material invisible as the aim of poetry'. Through this process the elevation of things comes about. Cezanne and Van Gogh elevated things by means of colour in their paintings. In the case of Van Bakel and the artists who work with technology the constructions reveal their own elevation as transformers of 'technological matter' into immateriality. Because these constructions are elevated they refer us to new mental worlds. And this effect, that occurs during a minute passage of time gives Van Bakel's work its own particular significance. An ambitious synthesis that gives one a momentary glimpse of the process by which ideas and mechanics can combine to produce poetic power. When one looks at them carefully all of Van Bakel's works have the appearance of an unusual and very precise 'theatre of ideas' based on physics. Once again there is a distant comparison with the often theatrical character of 18th and 19th century experiments in physics, such as those of Galvani, Marum, Dalibar or Tesla and which at the present time might make successful 'performances'. He works with the tempo of the seasons, of changes in climate, with the time of nature itself and in this way he draws a parallel with the elementary stuff that the world is made of and which operates as it were in a concentrated fashion in the odd combinations of earthly materials that he uses for his artistic mechanics. Matter is itself permitted to demonstrate how it recreates the spirit of its creator. And not only within the context of a single work of art, but often as a chain of objects conceived one after another (for instance, 'The Pole Star Telescope' and the 'Perseids Telescope', or 'Book V from our series of difficult books: Mechanica'.) Temperature, time and language (as we can see from his elaborate titles) play the lead roles in his spatial constructions. And this is where Van Bakel's mechanics, specifically because of its emphasis on an 'inert' time, converges with the tendency in the new art to introduce the principle of dynamics. A gradual refocussing on the element of time. A shift in attention away from the Copernican notion of space-which prevailed in the Renaissance and had a revolutionary influence on the art of that time-towards the constant mutability of the 'society of fast and ultrafast mechanisms '.6 An art that leaves its traditional static language of forms behind as it becomes conscious of the changing structure of society produced by technological innovation. A new art that does not so much look back with longing to the age of alchemy, but which is forced to respond to the fascinating developments within technology and scientific thinking and that aims to be part of 'the great speeding-up process, the coming reign of the element of time'. A refocussing that has occurred in art history on other occasions and which usually has the function of putting things in a new perspective; a good example inmusic, for instance, was the heroic attempt of the composer J.S. Bach to compress the old system of notes into an equal temperament scale that would provide a solid basis for the spatial deployment of classical and modern music that took place later. Meanwhile I was once more driving through de Achterhoek where I was staying last week. After Zutphen I turned left down a small country road in the direction of the village of Almen. Not far from the village I came to a halt in the wooded countryside where the castle of Almen nestles. I stepped out. The evening breeze soon cooled my cheeks and the smell of Autumn hovered round the leaves that were whirling around as I walked up the drive. After walking past the little silent pond with its dark reflection in between the tall ancient trees I came to the country house. The lights were on inside. I stood in front of the iron fence and looked at the 18th century house that stood safely tucked away in the surrounding 18th century landscape. As I gazed at the lighted windows I saw a woman's shape moving. The baroness was at home. The chilly gusts of wind made me shiver in my jacket and I walked along the path round the edge of the estate towards the old lift bridge over the little river Berkel. I sat down on the bench by the river and looked at the dark water flowing slowly past.The sky was clear and there was still some light in the West. The misty silhouette of the tower of Almen rose above the distant line of trees that was now rapidly beginning to merge with the night sky. Being alone like this in a broad dark meadow is very relaxing. One's alienation from things vanishes. But a certain increased sensitivity and watchfulness takes its place. One notices every sound or movement and this makes for a slight feeling of unease. Inherited fear of the natural world that is too close at hand? Gerrit had been talking about fear that very afternoon. I cannot remember the precise train of our conversation. It made us laugh. Fear and mathematics! Now I remembered... Fear and mathematics? Whatever next? I couldn't immediately imagine what he was on about. Gerrit had no doubt formulated an elaborate psycho-mechanical-aesthetic theory about it. If that were the case it would not be the last that I would hear of it. An attractive idea, for that matter, a relationship between the ratios of mathematics and negative feeling. Descartes also felt afraid after the dreams he had had that led to his method. Afterwards he prayed and promised to make a pilgrimage. Quite an odd response to what would be the first step in the methodical mathematicizing of the world that we now rejoice in. Gerrit's works of art are also very mathematical....and courageous. Spiritual and poetic courage as a remedy for the fear of an already totally mathematicized world? He however talked about mathematics itself as being a form of fear. Mathematics that in its multiformity and omnipotence has come between us and the world and which has alienated us from ourselves methodically and from within, has made us lose our own 'being'. Can art which has itself for a long time been under the influence of mathematical thinking reduce this distance once again? Or is there little else left for us except to change with it, to follow through with the ever-increasing sophistication and differentiation of the world and its objects and to allow oneself to be completely swallowed up in new language-based ultra-complex organizations? I would have to talk to him about it another time. Looking up towards the black open space of the night sky I looked for the points that Gerrit had pointed his telescopes at. A universe up there that is still young, expanding majestically but vibrating with restrained excitement. What an extraordinarily relaxing idea. What promise! The wind blew colder from across the river and I got up from the bench. The narrow winding path took me back to the old castle. I peered again through the fence in the direction of the silent stately home. The baroness had drawn the curtains across the high windows and I walked, a simple man, back along the dark drive. Victor Wentinck, Autumn 1991 The composer Victor Wentinck (born 1948) studied electronic composition at the Royal Conservatory in the Hague. In 1972 he established the electronic studio at the Brabant conservatory in Tilburg. From 1972 until 1973 he teached electronic music at the Royal Conservatory in the Hague and from 1970 until 1982 he worked at the foundation STEIM (studio for electronic music) in Amsterdam. In 1984 he founded the organisational office for new music, 'Ooyevaer Desk', of which he is director. Noten: 1. Van Bakel made an odd miscalculation (or exaggeration), because with a speed of 18 mm. per day it would only take 17000 years to cover 1100 km. |

|||||||||||||||||

|

|

|||||||||||||||||